Windows Server Event Log for most teams are only used when something already smells like incident:

💥 DC misbehaving,

💥 file server “mysteriously slow”,

💥 SOC asking for “all the logs you have from last week”.

Table of Contents

Until the moment of investigation, the Event Log is treated like a legacy detail from the Windows 2003 era and to be honest, it does look like from that time. It also is configured with defaults for servers with CPU, RAM and storage from the year 2003, so let’s look into it with our eyes from today.

What you’ll get from this article about Windows Server Event Log

If you run Windows servers (on-prem, Azure, Arc, Edge – doesn’t matter), you’ll get:

- A short mental model of the important Windows Event Logs

- A practical view on Event Log policies and where the knobs live

- Concrete starting points for log size and retention

- A final chapter on Sysmon from Sysinternals – and why you should care if you’re serious about detection

Event Logs: What you should know

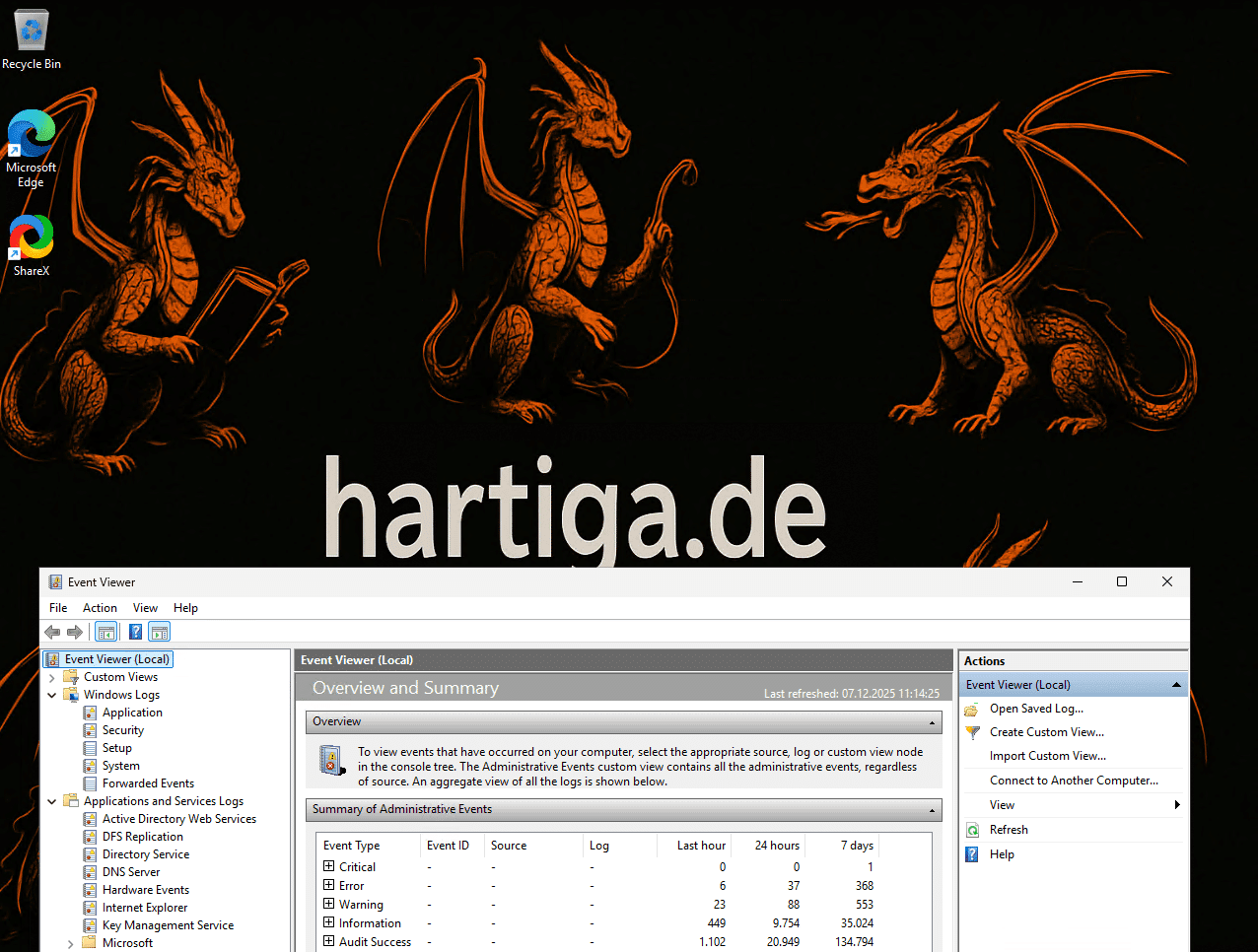

When you open Event Viewer on a server, there are two worlds:

- The “classic” Windows Logs

- The more granular Applications and Services Logs

Windows Logs – the baseline view

These are the ones most admins know:

- Application

Events from applications and services on that server. If your line-of-business service crashes or throws .NET exceptions, it usually lands here. - Security

Your audit trail: logons, access checks, group changes, privilege use, etc. If you ever have to reconstruct “who did what when” on a Windows box, you start here. - Setup

Installation and setup events – roles, features, some DC/AD related operations. - System

OS and core service health: drivers, service failures, network stack issues, storage problems. - Forwarded Events

Logs coming from other machines via Windows Event Forwarding (WEF). Very handy if you don’t have a full SIEM yet.

Reality check:

Most teams only really look at Application, System and occasionally Security. But if you care about security or forensics, Security + proper policies are non-negotiable.

Applications and Services Logs – where the modern detail lives

Below “Windows Logs” sits Applications and Services Logs. This is where individual components and features write their own logs, with four sub-types:

- Admin – “Something broke, here’s the error and what you can do.”

- Operational – Designed for trend analysis and troubleshooting. Perfect for building alerts.

- Analytic – Very high volume, fine-grained, off by default. For deep dives only.

- Debug – For developers and very specific troubleshooting.

Analytic and Debug logs are hidden and disabled by default; you have to enable them manually in Event Viewer when you actually need that level of noise.

What are Event Log Policies

The interesting part is not just reading logs – it’s controlling how they behave:

- How big they are

- How long they keep data

- What happens when they are full

- Who is allowed to read or clear them

On a domain-joined server, you usually control this via Group Policy:

Computer Configuration→Policies→Administrative Templates→Windows Components→Event Log Service

Under Event Log Service you’ll find policy sets for:

- Application

- Security

- Setup

- System

All four have almost identical settings – think of them as four separate dashboards for the four classic logs.

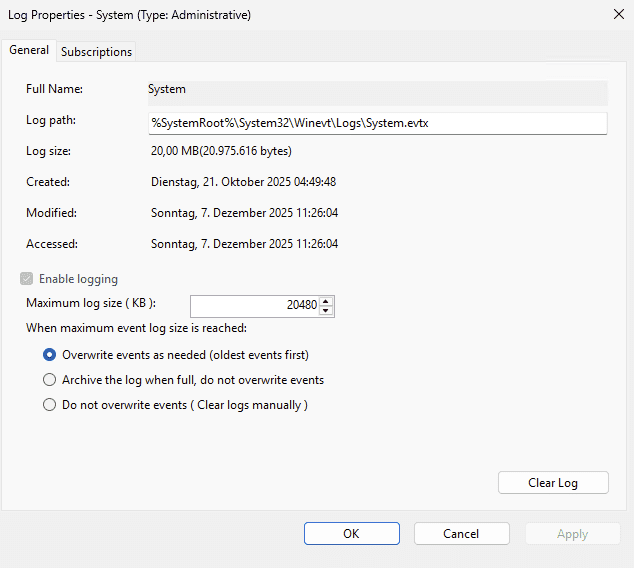

Windows Server Event Log Maximum log size – 20 MB is enough

On a fresh system where nobody touched the defaults, Windows Event Logs are often tiny. Historically this was on the order of 1–20 MB, which made sense when disk was expensive and servers weren’t doing much.

In 2025, that’s not serious.

Microsoft’s policy documentation for Event Log Service gives us the real range:

you can set the maximum log file size between 1 MB and 2 TB (1024–2,147,483,647 KB), in KB increments.

If you actually enable proper auditing and have a bit of load on your DCs or file servers, you’ll blow through a few dozen MB in no time.

My rough way to size logs:

Average event size (~500 bytes) × events per day × days of history you want on-boxImportant: You won’t hit the perfect number on day one, but you’ll be far better than the defaults. Keep monitoring this.

My usual starting points:

- Homelab / small environment

- Security: 512 MB – 1 GB

- System & Application: 256–512 MB

- Larger / regulated environment

- Security on DCs and critical servers: 1–4 GB on-box,

plus proper forwarding into SIEM / Azure Monitor / Sentinel / Splunk / … for long-term retention.

- Security on DCs and critical servers: 1–4 GB on-box,

You set this via policy:

Event Log Service → <Log Name> → Specify the maximum log file size (KB)

or the Windows Server Event Log Viewer GUI -> Click on the Log Name -> Properties

What happens when the Windows Server Event Log is full?

This is where a lot of environments quietly break their own logging.

The policy behind it in the ADMX world is called:

Control Event Log behavior when the log file reaches its maximum size

Plus there are related settings like:

- Backup log automatically when full

- Retain old events

Between these, you effectively choose between three behaviours:

- Overwrite events as needed (rolling log)

- New entries overwrite the oldest ones in the same file.

- Default if you don’t enable the “control behavior” policy.

- Works well if:

- your logs are reasonably sized, and

- you also forward important events centrally.

- Archive and start new file

- When the log is full, Windows closes it, optionally backs it up, and creates a new empty file.

- Good when regulations or internal policy demand that you keep full on-disk history for some time.

- Stop logging when full (don’t overwrite / don’t archive)

- If you enable the “Control Event Log behavior…” policy in the CSP/ADMX sense and choose the wrong option, new events are simply dropped once the log is full.

- This looks “secure” in theory (“we preserve all logs”) but is disastrous if you don’t permanently babysit log size and disk usage.

And then there is the dangerous but sometimes a security requirement. Only enable this when it is a hard requirement by your security teams.

Audit: Shut down system immediately if unable to log security audits

That one lives under Advanced Audit Policy, not the Event Log Service node, but it ties directly into log capacity: if the Security log can’t accept events, the machine shuts down rather than run without audit. Great for some Tier-0 workloads. Catastrophic if you undersize the Security log on a domain controller.

Where the Windows Server Event Log live – and why you might move them

By default, the .evtx files live under:

%WinDir%\System32\winevt\Logs

You can change this per log:

- Event Viewer → right-click log → Properties → Log path, or

- via the “Control the location of the log file” GPO per log.

Why would you move them?

- Keep logs off the system drive

- Put them on a dedicated volume with more space

- Place them on storage that’s easier to back up in a certain way

But: if that volume isn’t mounted or fails, events are lost. So treat log storage like you treat database disks – not an afterthought. Never place them on temp volumes of Azure VMs.

Who can read or clear which log?

Out of the box, Windows applies sensible defaults:

- Security log

- Only Local System and administrators can read or clear it.

- System log

- System and admins can write/clear; authenticated users can read.

- Application & Setup

- Authenticated users have read access by default.

You can override this with the Configure log access policy per log. That requires setting an SDDL string (security descriptor) instead of just picking groups in a GUI, which is powerful but easy to mess up.

My pragmatic recommendations:

- Keep clearing Security log restricted to a very small admin group.

- Be mindful that read access to Security + relevant Operational logs gives a very deep view into what’s happening on your servers and in your AD.

Beyond the built-ins: Sysmon as your advanced sensor

Up to this point we talked about what Windows itself logs. That’s enough for basic troubleshooting and some security visibility. But if you want to know what’s really going on on a system – process trees, weird network connections, suspicious registry changes – the built-in logs run out of detail.

That’s where Sysmon (System Monitor) from the Sysinternals suite comes in.

What Sysmon actually is

Sysmon is a Windows system service and driver that:

- Installs once and survives reboots

- Logs detailed activity into its own event log channel

- Focuses on things like:

- Process creation and parent/child relationships

- Network connections made by processes

- File creation time changes

- Registry modifications

- Driver and image (DLL) loads

- WMI activity and named pipes (depending on config)

All of that lands in the Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon/Operational log under Applications and Services Logs. It’s still “just” Windows Event Log under the hood – but with far richer data.

Sysmon doesn’t block or prevent attacks. It’s a sensor – perfect for detection engineering, threat hunting and proper incident response.

Installing Sysmon: the short version

This is a very short summary. You will want to deploy this in automated fashion.

- Download Sysmon

- From the official Sysinternals page.

- Extract it to a folder (e.g.

C:\Tools\Sysmon).

- Pick a good configuration file

- Sysmon is useless without a config.

- A popular and well-maintained starting point is the SwiftOnSecurity Sysmon config on GitHub.

- These community configs encode years of tuning so you don’t drown in noise on day one.

- Install with that config

Example (simplified):sysmon64.exe -accepteula -i sysmonconfig-export.xmlThis:- Accepts the EULA,

- Installs Sysmon as a service,

- Applies your chosen config in one go.

- Verify that events arrive

- Open Event Viewer → Applications and Services Logs → Microsoft → Windows → Sysmon → Operational.

- You should start seeing events like:

- Event ID 1: Process creation

- Event ID 3: Network connection

- Event ID 11: File creation

- Forward Sysmon events centrally

- Configure your SIEM / log solution to ingest the Sysmon Operational log.

- This is where it becomes really valuable: correlation across servers and time.

Why bother with Sysmon if we already have Security log?

The Windows Security log tells you that something happened from a security perspective:

- A user logged on

- A group membership changed

- A file share was accessed

Sysmon gives you the technical detail behind it:

- Which exact executable ran with which command line, parent process and hash

- Which process opened which outbound connection to which IP

- Which binary or DLL got dropped on disk just before that weird behaviour happened

That’s the difference between “we see something odd” and “we can explain the attack chain step by step”.

Practical guidance for using Sysmon in 2025

Some of my learnings include:

- Don’t roll your own config on day one.

Start with a battle-tested community config from GitHub and then tune for your environment. - Deploy it where it matters first.

- Domain Controllers and Tier-0 systems

- Jump hosts / admin workstations

- Internet-facing servers

Then roll out more widely.

- Plan for storage and pipeline impact.

Sysmon is verbose by design. Make sure your SIEM and storage can handle the additional events – or tune down what you don’t need. - Use it for real work, not checkbox security.

Build concrete detections:- Suspicious PowerShell with encoded commands

- LOLBins abuse (regsvr32, rundll32, mshta, etc.)

- Unusual outbound connections from servers that normally shouldn’t “talk to the world”

Sysmon plus a well-configured Security log is a strong combination. One tells you what the system did, the other tells you what the platform thinks about it.

Summary – Event Logs are not only for the Security Team

In a modern hybrid world – Azure, on-prem, “Adaptive Cloud”, or just a glorified homelab – you need three things in order.

First, get your Event Logs to a sane baseline. Give them real sizes instead of legacy defaults, define sensible behaviour for what happens when logs are full, and be explicit about who is allowed to read and, more importantly, clear which logs. You won’t hit the perfect numbers on day one, but you’ll be several orders of magnitude better than running with factory settings.

Second, get the data off the boxes. For smaller environments, Windows Event Forwarding is perfectly fine to get a central view. As soon as things get a bit larger or more critical, those logs belong in a proper central log or SIEM platform – Sentinel, Splunk, Elastic, whatever is standard in your world.

Third, deploy Sysmon everywhere you care about attacks, not just outages: domain controllers, Tier-0 systems, jump hosts, internet-facing workloads. Start from a solid community configuration and tune it for your environment – but don’t just click “next, next, finish” with the defaults.

At that point, you’ve moved from “we open Event Viewer when something is on fire” to “this is a deliberate part of our infrastructure design”. And that’s exactly where it should be.

If you have any questions please don’t hesitate to reach out to me on LinkedIn, Bluesky or check my newly created Adaptive Cloud community on Reddit.

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andreas-hartig/

Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/hartiga.de

Adaptive Cloud community on Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/AdaptiveCloud/

References, more information and sources

Microsoft ITOps Talk blog + video: Microsoft Blog + Youtube

Sysinternals Sysmon documentation: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/downloads/sysmon

How to set event log security locally or by using Group Policy